Since movies have been around since the late 19th century, we often forget just how revolutionary they were. It must have been astounding to witness the first successes at capturing not just still pictures, but action. I’ve always found it interesting that the term for movies with sound—“talkies”—never permanently caught on. It’s the action that everyone craves, and, indeed, our brains are incredibly adept at recognizing it.

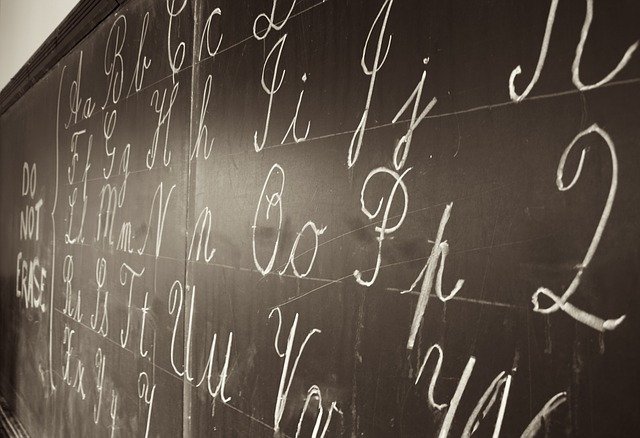

When it comes to language, our love of action is encapsulated in the verb, which is the heart of a sentence. In English, only one type of word can make a grammatically complete one-word sentence: the verb, in imperative (command) sentences such as

Go!

Come!

The subject, or actor, in sentences like these is an unspoken but understood you.

It’s this focus on action that gives verbs their power. Besides giving it a name, verbs also fix action in time in the past, present, or future, and also tell us how many actors are involved—one or more. Of course, the how many (“number,” in grammatical terms) has to match between the verb and its subject or subjects.

Let’s take a few installments to dive deeper into verbs, starting with this last point: making sure verbs agree in number—singular or plural—with the subject. Sometimes problems come up when it’s difficult to determine what the true subject of the sentence is:

Hollywood’s output of memorable, well-crafted movies has declined in recent years.

Do the subject and verb agree in number here? It might be a little difficult to tell at first, but the answer is yes. At first glance the words …movies has… might seem odd, until you go back to find the true subject of the sentence. The phrase of memorable, well-crafted movies describes output, which is actually the subject. If you remove that phrase, you’re left with

Hollywood’s output has declined in recent years.

Now the subject-verb agreement is much more visible: the singular subject output with the singular verb has declined. So removing any modifiers which might obscure the true subject is a good way to check.

If you’d like to review in more depth how to find the true subject of a sentence, check out this previous post.

Compound subjects

What if you have more than one subject in a sentence? It’s simple when you have and linking them: the subject automatically becomes plural and thus takes a plural verb:

Casablanca and A Clockwork Orange are two of my favorite movies.

But what about the words or and nor, which are not inclusive like and? Here we have three possibilities:

If both subjects are singular, use a singular verb: An actor or a director is allowed to use the studio canteen.

If both subjects are plural, use a plural verb: But neither tourists nor the cleaning staff are permitted.

If you have a combination of a singular and a plural subject, the verb should agree with whichever subject is closest to it: Neither the director nor the actors were happy about the project’s cancellation. (The plural word actors is closer to the verb, so it must also be plural.) This also works when the subjects are paired with not only…but also: Not only trailers but also a public service announcement was shown before the movie started. (The singular word announcement is closer to the verb, so it must also be singular.)

Subjects that can be either singular or plural

Don’t worry, this isn’t as confusing as it might sound. We’re talking about words like couple, total, majority, and number. Sometimes they mean the group as a whole, in which case they are singular and take a singular verb. Here’s a hint: if the word is preceded by the, it’s most likely singular:

The number of movie scripts that never make it to production is astonishing. (Note that this sentence is also a good exercise in determining the real subject—the number. The other words between it and the verb is merely describe number.)

However, if you have a before the word, and especially if it’s followed by of, it’s probably plural and will take a plural verb:

A majority of moviegoers believe that ticket prices are too high.

Another group of words that can be either singular or plural is all, any, and none. Here’s a trick that’s very helpful with these three: think about what is implied. If the sense is all of it, any of it, or none of it—since it is singular, you need a singular verb:

All the movie’s budget was spent before filming was finished. (The sense is all of it, i.e., the budget, so the verb is singular.)

But if the implication is all of them, any of them, none of them—since them is plural, you need a plural verb:

None of the critics are pleased with the new film. (The sense is none of them, i.e., the critics, so the verb is plural.)

I think this is enough for this time around to get us started. But I’ll be back in the next installment with more words that can be either singular or plural, depending on the context, and how to figure that out. In the meantime, practice with the ones we’ve covered here, and look for examples “in the wild” in your reading. Were they all used correctly? Please feel free to share any interesting examples you find below!